Early Childhood Education, K-12 Education

Two Systems, One Family: The Lived Reality of America’s Educational Divide

While policymakers often debate early childhood and K–12 separately, families experience them as one continuous journey — full of hopes, tradeoffs, and structural contradictions. Over the coming weeks, this series will unpack how we arrived here, how these systems are evolving, and what it would take to design a more coherent pathway for every child.

A working mother sits at her kitchen table after bedtime, far too many tabs open on her computer. She’s trying to sort out child care for her almost-three-year-old, deciphering program types, weighing cost and availability, mapping commutes, comparing hours to her work schedule. The waitlists are long — so long — for the programs that actually fit her life.

What’s a mom to do?

Her mind wanders ahead to Kindergarten. She scrolls through neighborhood school reviews, tries to interpret the school’s report card, and reminds herself that at least – finally – her daughter will have a guaranteed spot somewhere. That brings relief, but also uncertainty: What does she really know about this school? Will it be right for her child?

This contrast isn’t just emotional. It’s structural. It’s the lived reality of America’s educational divide.

Before age five, parents act as consumers in a market system – empowered in theory to choose, but with no guarantee of access. They chase openings. They juggle waitlists and subsidies. They compare home-based care, center-based care, preschool programs, willing and able family members, and whomever might have a slot.

At age five, everything changes. Children enter Kindergarten and become beneficiaries of a public system. They receive guaranteed access to a seat – usually tied to their address – with limited but growing opportunities to customize.

Families don’t experience their children in silos. Their needs and values don’t shift overnight. Yet our system forces them to code-switch at age five—from navigating a fragmented early childhood market to entering a structured public K–12 system.

Understanding the Structural Divide

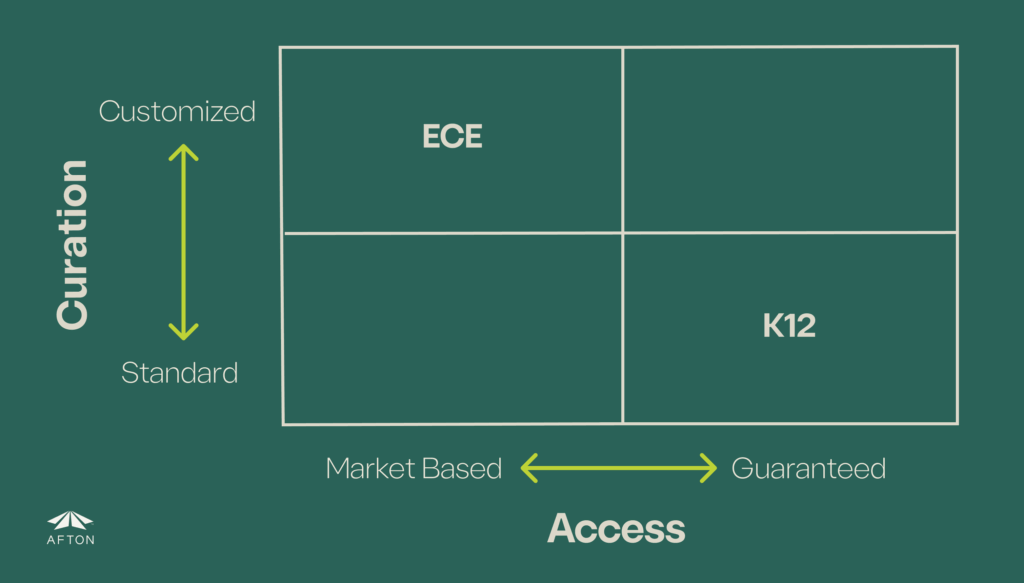

To understand this structural divide, we can use a simple framework that clarifies how each system is built at its core — independent of current reforms or policy debates. We’ll explore historical context next, but for now, consider our systems along two dimensions:

The X-Axis: Access

- Market-Based Access: In a market model, competitive forces determine where resources flow, and families access services based on price and availability. In our context, families match with available slots based on a variety of factors (e.g. timing of application, lottery, location, etc.). Access depends on navigating supply and demand.

- Guaranteed Access: Every child has an unconditional right to a slot (often based on assigned location) for free and compulsory public services, regardless of background or needs. The system bears responsibility for providing space and services regardless of demand.

The Y-Axis: Degree of Curation

- Customized: Families can design individualized learning journeys, selecting from various learning environments, pedagogies, curricula, locations, schedules, etc. to match their children’s needs and family priorities.

- Standardized: Educational experiences prioritize uniform guidelines and expectations for what students should learn, how it should be taught, and how they are assessed. Consistency is prioritized over customization to achieve goals.

The Current Landscape

- ECE (Upper Left Quadrant): High customization potential through market-based access. Families can theoretically choose providers matching their needs and preferences (if they can afford it and spots exist). ECE functions like a market, albeit with strong regulatory and subsidy overlays.

- K-12 (Lower Right Quadrant): Historically, K12 has offered guaranteed access with standardized delivery at its core. Every child gets a seat, but most families get their assigned district school with standard hours, pedagogy, and curriculum. While choice is increasingly available, latest data from Pew Research Center suggests that out of the entire K–12 school population, about 83% are attending a traditional public schools (though some of these are exercising choice within their public school district, such as magnet or open enrollment options).

The Critical Enabler: Capacity and Infrastructure

What this framework risks obscuring is a critical truth: customization depends on capacity on both the supply side and the demand side. And capacity (an organization’s resources) depends on infrastructure (structures and systems that make it possible to use capacity productively). These are market enablers needed to achieve goals.

Consider that on the supply side, providers need start-up funding and incubation time to develop new offerings, and they need wherewithal to understand family needs and preferences, the capability to design targeted offerings, get those offerings to families, and to sustain them over time.

On the demand side, families’ ability to curate a learning journey demands time, system knowledge, social capital, and financial resources — things most often associated with higher income families. This is where market enablers (such as navigation support, transparent and user-friendly information, simplified application and enrollment systems, and supports to overcome logistical barriers like transportation) becomes essential— not as a static feature, but as a dynamic force that changes through a family’s unique educational journey.

The depth and quality of infrastructure and family support determines whether “choice” is real or illusory, whether customization serves all families or only the privileged. As both systems converge — seeking to combine guaranteed access with meaningful personalization — this support becomes the determining factor in whether this convergence promotes equitable access to quality in both ECE and K12, or exacerbates inequity in both.

The Central Questions This Raises

We understand the structural hurdles built over centuries that have gotten us to where we are today. But if we asked families what they need, the answer would likely fall out like this: reliable access to quality education services that fit their children’s needs, without undue burden.

If families want guaranteed access with meaningful ability to customize, how can we build policies with that as the central goal?

This framework prompts four critical questions that must be understood:

- What works and fails in each quadrant? What do families gain from ECE’s market-based customization (choice but limited guarantee) versus K-12’s guaranteed standardization (access but limited customization)? What can the systems learn from each others’ strengths and mistakes?

- Where do families actually want to be? Is there alignment between where systems are moving and where families need them to be? How does this vary based on family resources? How do preferences change with capacity and infrastructure supports?

- How are both systems evolving across this matrix? Where is K-12 moving as it adds choice options? Where is ECE heading with a push for universal access? What early evidence do we see of what is taking hold and what is not, and why? How does this connect to family preferences?

- What does convergence mean for policy design? If both systems are moving toward some level of guaranteed access with customization options, what governance structures, funding mechanisms, infrastructure and supports must we build to promote equitable opportunities and meaningful outcomes?

This structural divide didn’t emerge by accident. It is the product of centuries of policy choices, cultural norms, and fragmented governance — forces that have shaped the systems families navigate today.

In the next installments of this series, we’ll briefly step back to trace that history and then look forward, examining where both early childhood and K–12 are headed and what convergence could mean for policy design. For now, it’s enough to recognize the core truth at the heart of this conversation: families deserve a system that meets them where they are, rather than requiring them to adapt to the system they inherit.