Reimagining the School Funding Adequacy Study

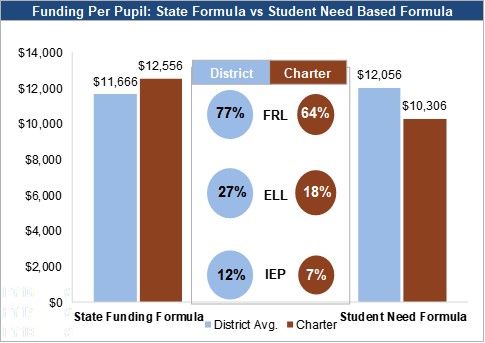

In 2023, the Washington D.C. Office of the Deputy Mayor of Education (DME) sought to re-examine how schools in D.C. are funded and how the existing funding structures serve students.

Over the past several years, D.C. has made great strides toward adequate and equitable funding, striving to ensure that students have the resources they need to succeed. Even so, persistent opportunity gaps exposed a need for further exploration, especially given that different funding levels targeted to needs did not easily explain those gaps. Why aren’t the investment levels lining up with outcomes?

In light of COVID-19 and other pressing external factors, it became clear that supporting students and families through a global pandemic and intergenerational poverty will take all of us. Schools have been asked to meet increasingly comprehensive needs, without the formal charge or funding structures to support that charge. What is the role of the school, and how can education and community leaders come together to provide the services and resources needed for brighter futures in their respective areas of influence? It was in this spirit of enduring commitment to continuous inquiry and improvement that led us to co-create an innovative approach to guide school leaders’ next steps.

Complex circumstances require a context-sensitive approach

Like many states, DC completes a periodic, legislatively required ‘funding adequacy study’ to determine the resources needed for students to meet standards. Adequacy studies go back to the 1990s as part of the standards-based movement, and the approaches remain in use today. While this history is an important foundation for school funding policies, The Deputy Mayor for Education (DME) saw the 2023 legislative requirement as an opportunity to think differently and partnered with Afton to collaboratively meet the moment. Given the complexity at hand, we knew we needed to examine the problem from multiple angles. We also knew we needed to engage the expertise of those most affected by—and yet also typically excluded from—policymaking decisions: students, families, and school communities.

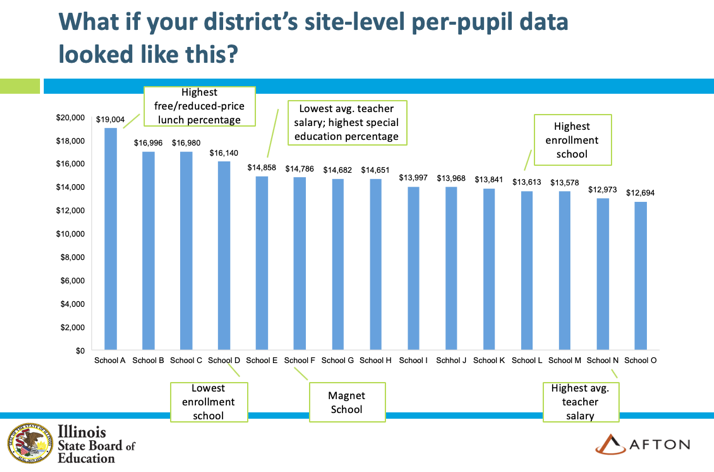

The desire for a data-informed understanding of current resource use and future resource needs led us to embark on a deep data exploration journey. As part of this journey, we developed archetypes of students and schools that helped us understand current funding and spending relative to student and community needs and outcomes at a far more nuanced level than is typical. This also positioned us to ensure adequate stakeholder representation across all archetypes developed, creating a ‘diverse by design’ approach to gathering input and feedback.

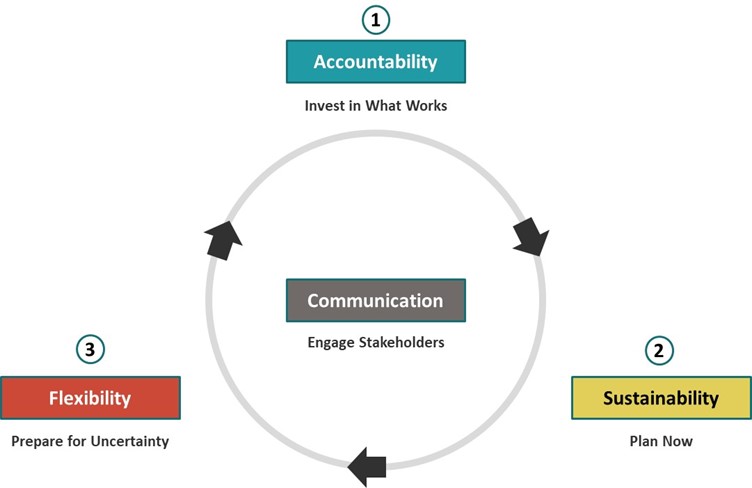

As a team, our desire to more fully understand the local context laid the foundation for a pioneering triangulation method that linked:

- national expertise, economic modeling, and quasi-experimental research findings;

- broad local stakeholder engagement from school leaders and staff, parents and caregivers, students, and community agencies; and

- deep data analysis on student demographics, needs, outcomes, and LEA- and school-level spending data.

This triangulation approach offered significant improvements to traditional adequacy study methods alone. While traditional methods– including the national Evidence-Based (EB) and Professional Judgement (PJ) panels– rightly form the foundation of this work, the triangulation of additional methodologies provides a richer understanding of needs and opportunities. Combining existing methods with deep student- and school-level data analysis and abundant stakeholder engagement allowed us to meaningfully incorporate the insights and wisdom of the students and families experiencing the system every day. While typical adequacy studies offer insight into how much should be spent, this study had a keen eye on how resources can be more effectively allocated. We could better understand student and resource needs at a more granular level than typical need categories, and then take several steps further to determine the appropriate level of local investment that would support those needs.

The substantial stakeholder engagement also provided a better basis for contextual recommendations. We were able to identify levers that can support LEAs and schools and ensure that dollars are spent efficiently and in a way that serves students most effectively.

A research approach that honors nuance, highlighting tensions and common ground

Triangulating the three methods brings out agreements and tensions in the data sets that otherwise may not surface. Where agreements exist, we can see elements of the problem in high contrast and know that it’s a clear pain point. Multiple lenses also can help clarify cause(s) and identify viable solutions. Where tensions exist, we’re better able to design solutions thoughtfully, with higher regard for the possible unintended consequences or trade-offs that we wouldn’t have known to be mindful of otherwise.

Stakeholder voice through school leader interviews and parent surveys helped us understand that schools were being asked to do more than they ever have and, in many cases, without the formal charge or necessary resources to meet those increased demands. Thanks to our triangulation method, we could immediately see that local data backed up that insight.

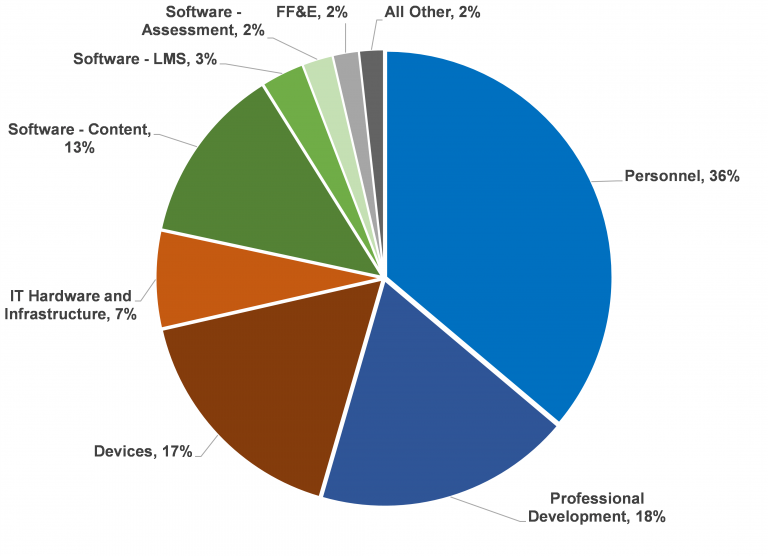

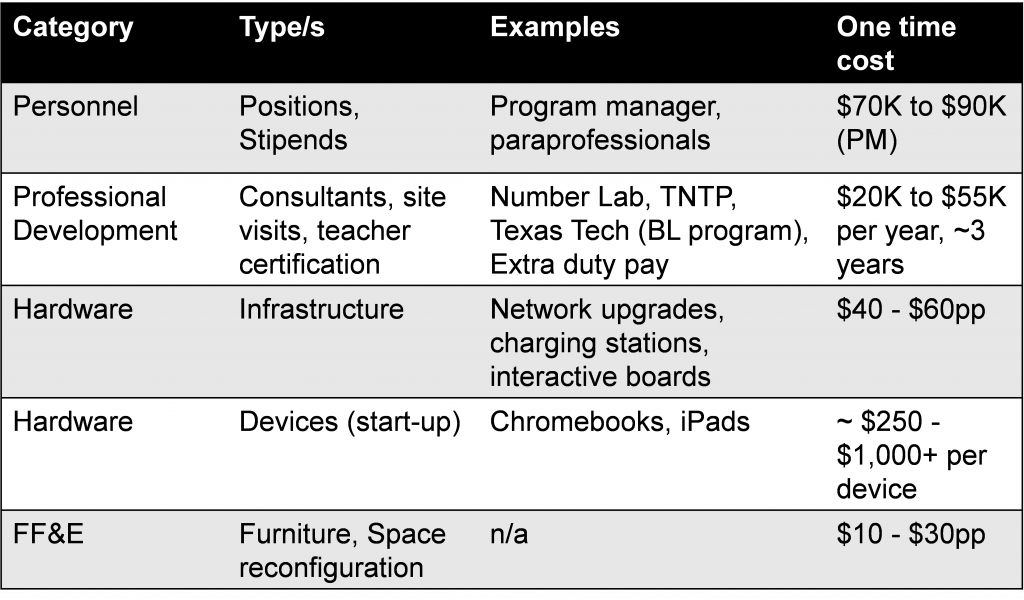

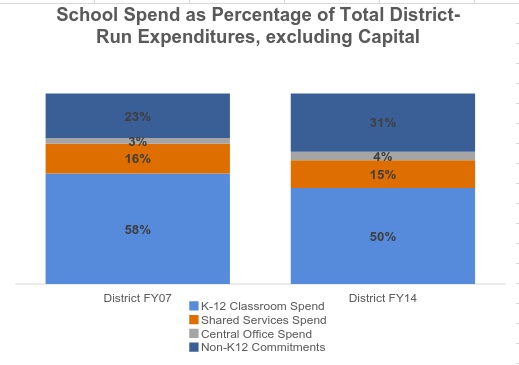

For instance: on average, schools spend less than 50% of their resources on instruction. Notably, schools with the highest needs often spent the least funding on instruction, as their student population required more non-instructional supports.

Our data also showed that resources spent on mental health support were high, relative to other spending. Even so, school leaders told us they would use extra dollars for additional mental health support and staffing, suggesting that their base resources did not adequately meet needs. Administrators also noted the increased demands of the teaching profession, expressing the desire to find ways to mitigate increasing burnout and turnover.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we heard from parents and families – across all wards and races – that they prioritize a positive academic reputation, highly qualified teachers, and a positive school culture. While we know from research these factors all directly impact student achievement, hearing directly from parents and families that they wanted to prioritize supportive measures to those ends created alignment. Leaders can now move towards pursuing well-informed additional investment and they strengthened the school-community connection having sought their valuable input on where the unmet needs exist.

A human-centered study facilitates better decision-making and promising outcomes

Our triangulation approach to the analysis provided a rich and diverse evidence base that informed a set of options and opportunities. Leaders are now equipped to make decisions for change that encompass immediately actionable shifts to funding levels within the funding formula, while also taking on related policy considerations to support change within and beyond the District.

In fact, change has already happened. Along with a 12.5% increase to the foundation level for teacher compensation, the weights within the funding formula are changing, too:

- The at-risk weight will increase from 0.24 to 0.300

- The alternative weight will increase from 1.52 to 1.58

- The adult weight will increase from 0.91 to 1.00

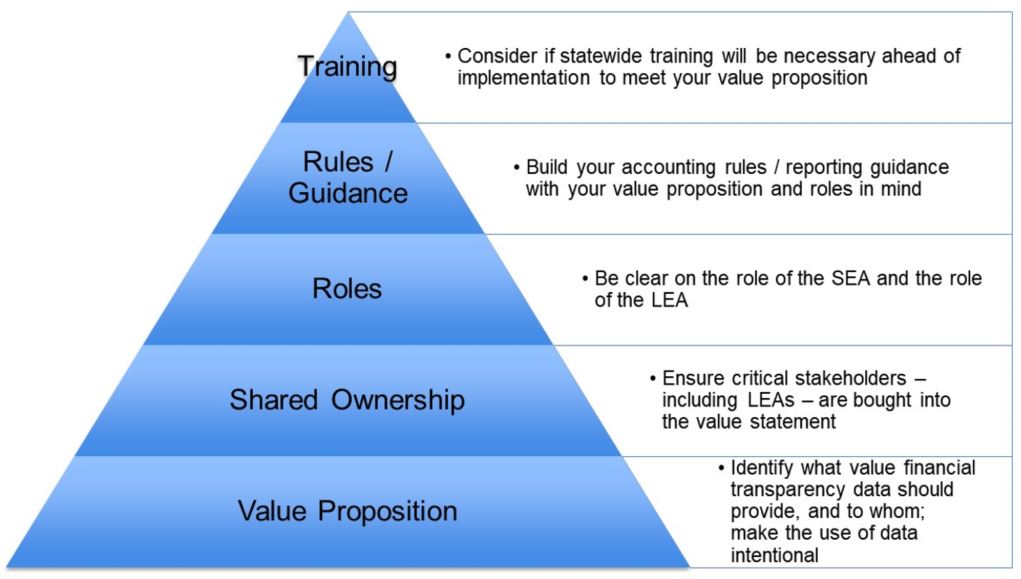

Beyond the funding formula, specific recommendations also surfaced for additional funding outside the funding formula. These recommendations included support for mental health services, teacher pipeline development, and pilot programs for a neighborhood-based approach to school transformation. We also recommended specific avenues for pursuing improved system efficiencies, as well as enhanced financial reporting and transparency to keep a keen eye on spending patterns as they relate to outcomes.

In addition to the published report of the full study, the work informed an interactive website customized to various users to support broad engagement with study approaches, findings, and recommendations in a human-centered way.

At Afton, we put people first. Doing so results in stronger research design, more nuanced insights, and better decision-making. We are proud to come alongside communities to co-create both problem-solving processes and actionable solutions in a way that respects and engages those who stand to be most impacted. Ready to get started on yours? Get in touch.