An Underfunded Mandate

The tumultuous years of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout created unprecedented academic, physical, mental, and social well-being challenges for students nationwide. NAEP scores provide ample data for what we feel: the academic impacts are severe and persistent, especially for students of color and low-income students. But these challenges are not new; many existed long before the pandemic. Indeed, we’ve been battling achievement gaps for years.

We know from extensive research that the factors that hamper post-pandemic learning recovery and ultimately widen gaps do not begin in the school. External factors such as family education and job opportunities, health, housing, transportation, food, and access to quality early learning influence a child’s readiness to learn. They exist as an indicator that multiple — and often siloed — systems are not adequately meeting needs, creating barriers to the opportunity to learn.

The most sophisticated programming and interventions will have limited impact if we don’t foster family and child well-being first. Wholesale shifts in governance, an aggressive push toward true student-centered learning, and intensive investments in proven evidence-based interventions all have merit and must be part of the solution set. But first we must name — and question — the unspoken mandate underpinning it all: are we asking schools to solve for multigenerational poverty and income inequality?

We must ask: What is the role of schools in addressing the root causes of achievement gaps? And are we equipping them — and funding them — to play that role?

If a complex web of systems, services, and supports keeps kids from being ready to learn, why are schools held solely accountable for closing the academic achievement gap? Test scores — which strongly correlate with indicators of family and community economic well-being, or lack thereof — reign supreme in school evaluation. They’re also often referred to as an imprecise proxy for school quality. But this is problematic: do a school’s scores truly reflect the quality of the education, or do they reflect the systemic challenges its students face, and that our public systems have yet to solve?

What’s a school leader to do?

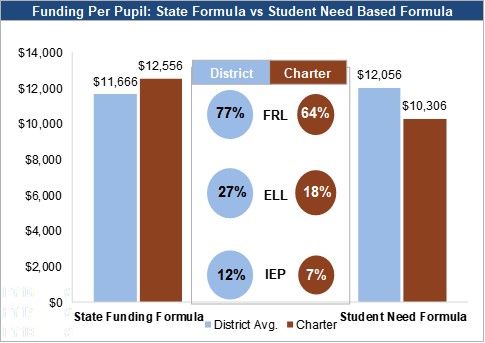

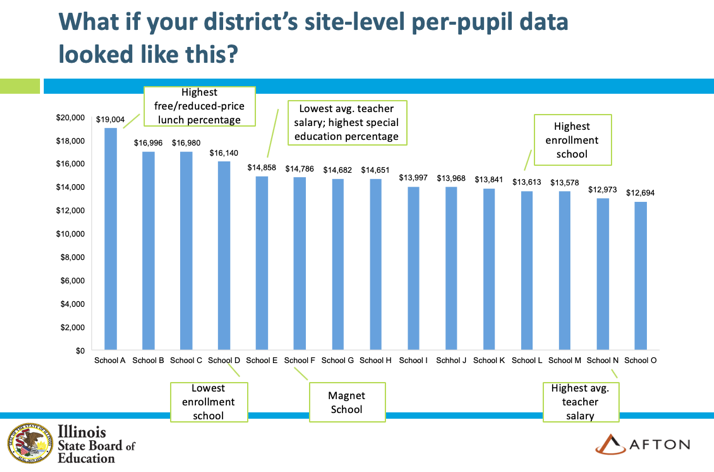

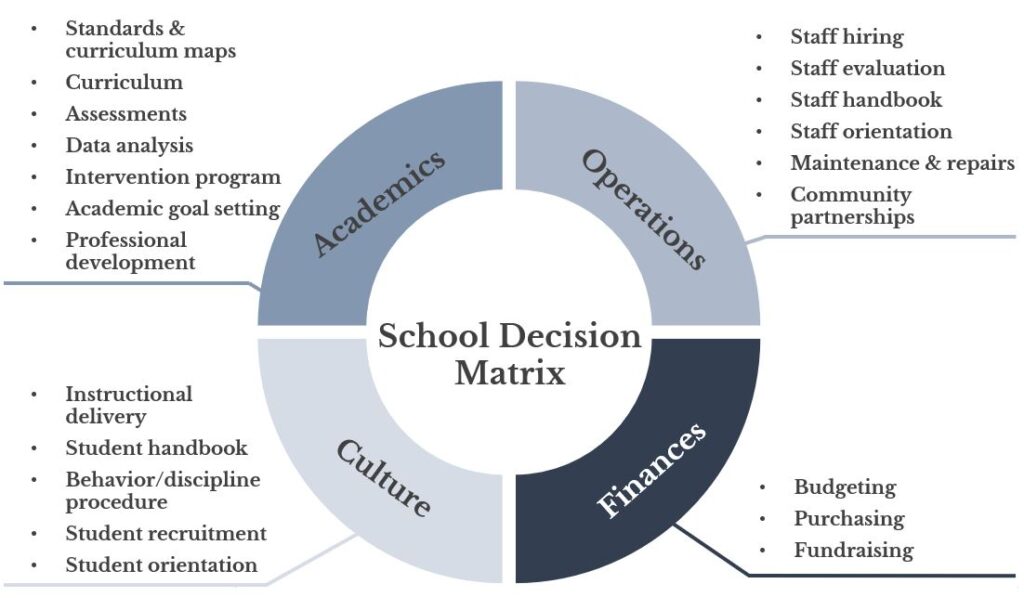

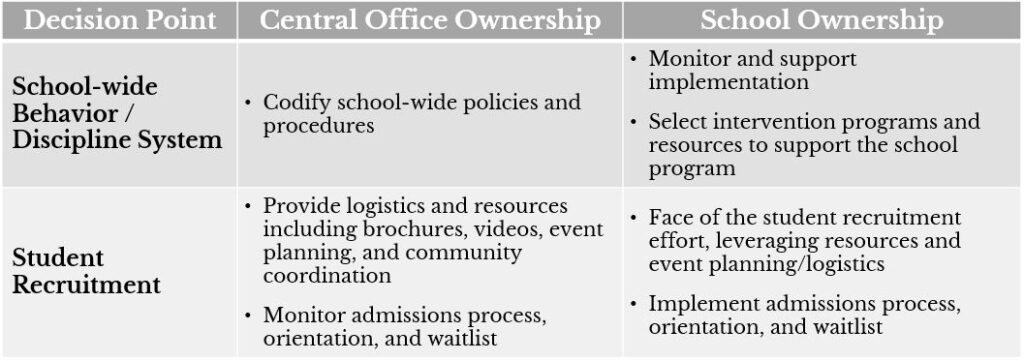

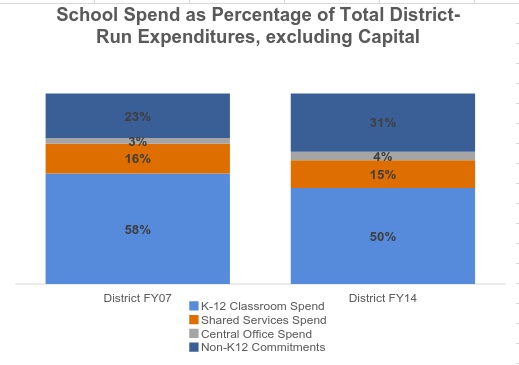

They’re put in a position to try and solve it all and “make the grade”. They do their best to put responsive programming and supports in place. They act as a safe and trusted resource in the community to parents and families. They do all they can within their sphere of influence to close the gap and meet the needs of poverty and trauma, in the interest of uplifting their students and carrying out their mission. In a 2023 study of school funding in DC, we found that schools are increasingly spending money on resources to ensure kids are ready and able to learn, such as social workers, psychologists, and climate and culture staff. And schools serving students with the highest needs are spending significantly more here.

But even in the most well-resourced schools, these efforts are not enough. And the unfortunate reality is that the schools most often put in a position to “solve it all” have historically been underfunded and under-resourced at baseline. Even our funding formula weights for low-income students don’t cover what research tells us low-income students need: statistical analyses indicate low-income (“at risk”) students could require more than three times the funding of their peers. Because, well, the cost is looks preposterous. But is it?

As one school leader put it,

“Schools have taken on an additional social services arm — not real wraparound services with trained individuals — everyone trying to piece things together to meet the needs. If the school is going to be the hub for the community — then it cannot be the school that is charged but doesn’t have the resources. If this is the expectation of schools, then that money needs to come to schools to support.”

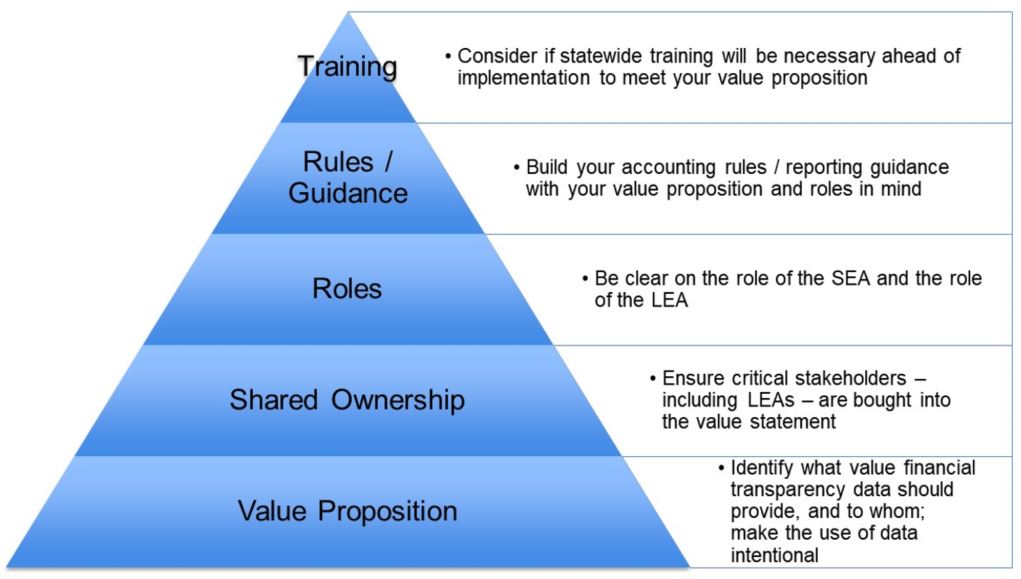

The overwhelming insight we’ve gathered from educators, families, and students grappling with these challenges is this: We need to start thinking holistically about services, supports, and resources beyond the walls of the school building. Interrelated challenges call for integrated solutions, shared ownership, and a revolutionized approach to resourcing. Children go to school within the context of their families and community and other systems, and failing to acknowledge the impact of those external factors will only ever allow schools to be partially successful in serving students well. Of course, schools have a role – a primary one – in closing academic achievement gaps. But it’s not their challenge alone. Instead of the persistent calling out of schools for missing the mark, let’s start calling in the broader system of services (and associated funding and resources) our kids need.

It’s time for a paradigm shift that leaves the idea of education as a “closed system” behind.

It’s time to stop expecting linear inputs and outputs from institutions that exist in a tangled web of interdependency. It’s time to approach student achievement as a function of multiple systems working together and alongside one another. It’s time to change how we frame the challenges, who gets a seat at the table, and how we think about accountability for outcomes. It’s time to start seeking answers to much harder questions than we’ve ever chosen to ask.

If you agree that it’s time, let’s start that conversation.